Designing Hitboxes and Hurtboxes for a Fighting Game

4532 Words : 20 Minutes, 36 Seconds

2025-09-06 09:31 +0000 [Last Modified on : 2025-09-08 08:55 +0000]

When you first get started with a fighting game, you will get tasked with creating hit/hurt-boxes and the question of where to even begin? Some things are obvious - you design them to loosely match the animation work of the characters. But even then “loosely” still leaves a lot of things you can edit and tweak. How long should you hold the active frames? How should you nudge the boxes’ positioning and size in relations to the animation frame? These are just some of the questions that may pop up.

What I do and what I would advocated for is designing the boxes of your game with games systems and dynamics in mind. Specifically - how to use boxes to create tools, counters and strategies that players could use and encourage specific type of play.

Designing Footsies

It is important to realise that footsies are a consequence of the boxes design. While early footsies may have developed naturally through the imitation of martial arts movements, the core rules of “good” footsies design are now well-established within the genre. Because this is the system that is most affected by the boxes design - I would focus on footsies here. Also a lot of the concepts here could be later adapted to other kinds of systems and situations that arise in fighting games (like the air game). In case you are not familiar with the term footsies I recommend this handbook by sonic hurricane.

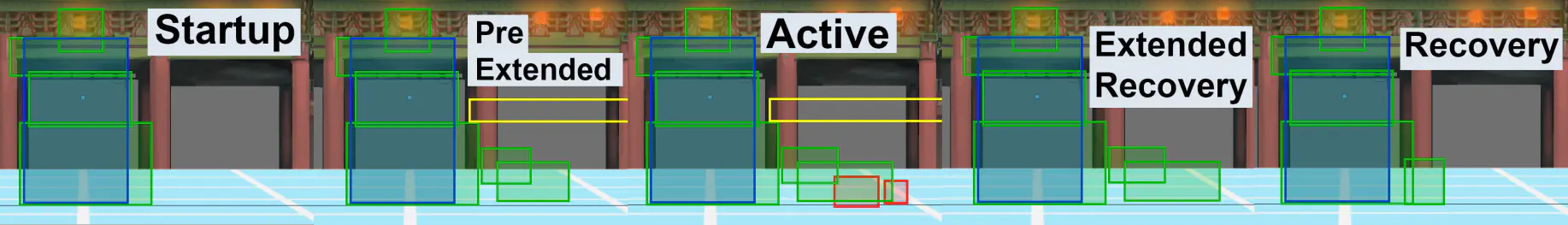

5 Parts of a move

I break up moves into 5 phases:

Startup

Those are the frames that lead from idle to the active portion of the move. The hurtboxes in this phase are either identical or close to identical to the idle hurtboxes.

Preextended

Those are the frames before the first active frames, where the limb is extended or starting to extend. They generally look like the idle hurtboxes (or the specific stance of the move) with an added hurtbox for the limb in front of the character. Some moves might gradually extend the hurtbox of the move so the discerning line between the Startup and the Preextended phase can be muddy. Preextended frames might also not exist, so this is an optional phase.

Active (and initial Active)

Those are the frames where the move can actually deal hit the opponent. The initial active frame generally has further extended hitbox, but it is not a mandatory addition.

Extended recovery

Those are the frames where the hitboxes of the move disappear (so they can no longer hit), but the hurtbox extension remains. Similar to the Preextended phase it is optional and can blend with the Recovery phase.

Recovery

Hurtbox is similar to the Startup phase, but at the end of the move instead. Main difference with Startup phase appears in moves that start standing, but finish crouching and vice versa.

Pokes - reach and movement speed

First main attribute to consider is the reach of different moves, how far away you can hit someone with your move. This is the main attribute for poking attacks - the better the reach the better the poke. This is done via the combination of how far the hitboxes reach forward, and also how far does the move moves you forward during the startup + preextended phases. There are several side effects to gaining reach via movement speed or via hitbox extension:

- Combo spacing - if you gain reach via movement speed you will be closer allowing you to potentially combo further moves. This is a double edge sword however, as if you get interrupted you will also be closer to your opponent allowing for more combo routes.

- Screen and pressure spacing - movement speed would win you more space, pushing you further away from your corner. It would also keep you closer to your opponent after you both recover.

Whiff Punishes - recovery, extended recovery and startup

The key phases that allow for whiff punishes to exist are the recoveries. If a move literally has no recovery frames whiff punishing would simply be impossible. There are 2 main concepts/attributes that are important for how easy a move is to whiff punish - spacing margin and timing window.

First of is the spacing margin, this is the range you have to be at in order to be able to whiff punish. You want to be just outside of their attack reach, but also you want to be within reach in order to hit their new position either due to the total movement speed of the move (the combined movement from all phases) or due to the extended hurtbox during the extended recovery phase. A key element that controls the spacing margin is the disjointness of the move - this is the margin between the reach of the hitboxes of the move and the “reach” of the hurtbox of the move. The bigger the disjoint the harder the move is to whiff punish and it might be even impossible.

As for the timing window it is for how many frames your opponent is exposed to getting attack without being able to block - it is almost equal to the sum of the recoveries durations. Something you should consider here is the startup of the move you are using to whiff punish as well (it would generally be some other poke), the longer the startup the smaller the timing window. In fact the spacing margin and the timing window are related, for example you might have a fast poking move that can ONLY hit your opponent during the extended recovery, so your timing window would be ONLY the extended recovery frames minus the fast poking move startup frames. On top of that the extended recovery and recovery phases might be muddy and the hurtboxes might gradually pull back, meaning that the spacing and timing gets coupled.

Another thing that might reduce the timing window are preextended frames of the move you are using to whiff punish with. If you are too close you might actually get clipped by your opponent’s active frames while you are trying to whiff punish them. This is also where initial active frames importance comes in. By having the initial active frame have bigger reach than the rest of the active frames, it allows you to have a poke with a specific reach, while also pulling back afterward to prevent clipping of whiff punish attempts, and increase the timing window in the process.

What you should also consider here are reaction windows. Reaction windows are counted from the moment the move is identifiable (you can recognise the attack and react to it) to the end of the timing window. 15f is around the average reaction time, however you should consider input lag in the equation as well. Also people would often react to multiple things so putting something at 15f would require the player to be fully focused on reacting to just that specific move - meaning it would be a HARD move to whiff punish on reaction, but possible.

On the other hand timing windows are about predictive play instead. As a reference Street Fighter 3 3rd Strike, has a parry window of 10f. The parry is used in a similar manner to a timed whiff punish, so this is a good predictive timing window to use as a baseline for something players would be able to consistently whiff punish with a good prediction.

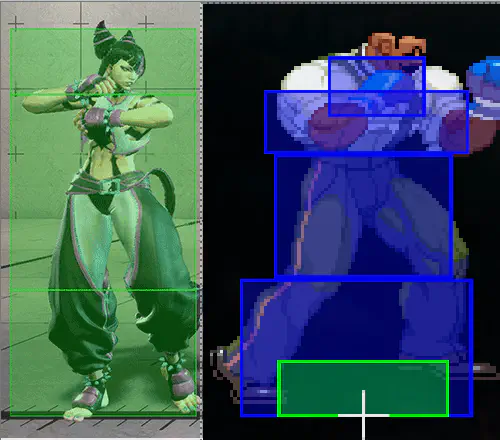

Counter Pokes - preextended hurtbox and attack hold

Counter pokes functions based on the preextended hurtboxes and on the movement displacement before the first active frames. Similar to the whiff punishes counter pokes have a timing window. The timing window of counter pokes is the sum of the preextended frames of the move being counter poked, and also the active frames of the counter poke move. Again you have some complications when we consider movement speed and gradual preextensions of the hurtbox. However counter pokes are generally used in a much closer range so spacing considerations are more lenient. The main thing you have to look out for is that the counter poke move can counter poke another move at its max range.

This is also where the initial active frames have a usage once again. Moves can and do have a dual purpose, so a counter poke move can double as a fast poke move. This way the reach of the initial active frames can be used to balance out the poking component of the move, and the held active frames afterwards with lower reach can be used to balance out the counter poke component of the move.

Something that can also help with the spacing is disjointed aspect of the moves. This way you can allow counter pokes to win trades. This is a balanced trade off since counter pokes cannot damage the opponent unless the opponent pokes, meaning the predictive responsibility is already on the counter poking player. Because of this giving them an advantage in counter poke scenarios can help out with making counter poking more consistent and intentional.

Some moves might even lack any preextended hurtbox, in which case the timing window is simply 0. This would make the move immune to counter poking and it is a very powerful property of a move to have. It can also lead to “checkmate” scenarios where one player can neither move away in order to whiff punish or stay and counter poke, leaving them with no other option, but to block. An example that comes to mind is SF6 Juri’s st.hp1.

Both frames are back to back.

Back when the game was released there were some spacing traps against Ryu, where Ryu has no option to beat this move except going for a DP, or an invulnerable move. It is up to you as a developer if you want those kind of checkmates in your game. I’m not against checkmates, but I personally avoid this kind, since I find this space trap way too easy too setup.

Cheat sheet

Here a short cheat sheet of attributes that are important to moves as they play different roles as poke, whiff punish and counter poke. Use those attributes to balance moves around, give them both strengths and weakness in various attributes. If you don’t have any weakness in the attributes the move would be uncountable and would become “broken”.

Poking attributes

- Better reach

- Higher disjoint (for lower spacing margin vs whiff punish)

- Fast recovery (for lower timing margin vs whiff punish)

- Small preextention and low amount of preextention frames (for lower timing margin vs counter pokes)

Whiff punisher attributes

- Better reach

- Fast startup

- Small preextention (minor importance)

Counter poke attributes

- Higher disjoint (to help with trades)

- Fast recovery (counter pokes are used predictively so having them be whiff punishable on reaction would make them close to unusable)

- Fast startup

- High amount of active frames

Going Beyond

Here a few examples of what you can get by pushing some attributes to the extremes:

- Fast super disjointed move with long recovery - DPs

- A simple example of move type with well defined strengths and weaknesses. It is a type of move that can be used for pretty much everything, but poking and can be super effective at it. However it is balanced by making them punishable on reaction, making them a gamble.

- Super high reach, but long “startup” - Tackles/Chariots/Charge moves

- While those moves can reach their active frames at relatively normal times, even if they do, they are generally not really extended much, meaning most other pokes and counter pokes with some amount of disjoint would win. Those kinds are practically immune to whiff punishing (you are not standing outside of their reach), and are instead beaten by counter poking - keepout.

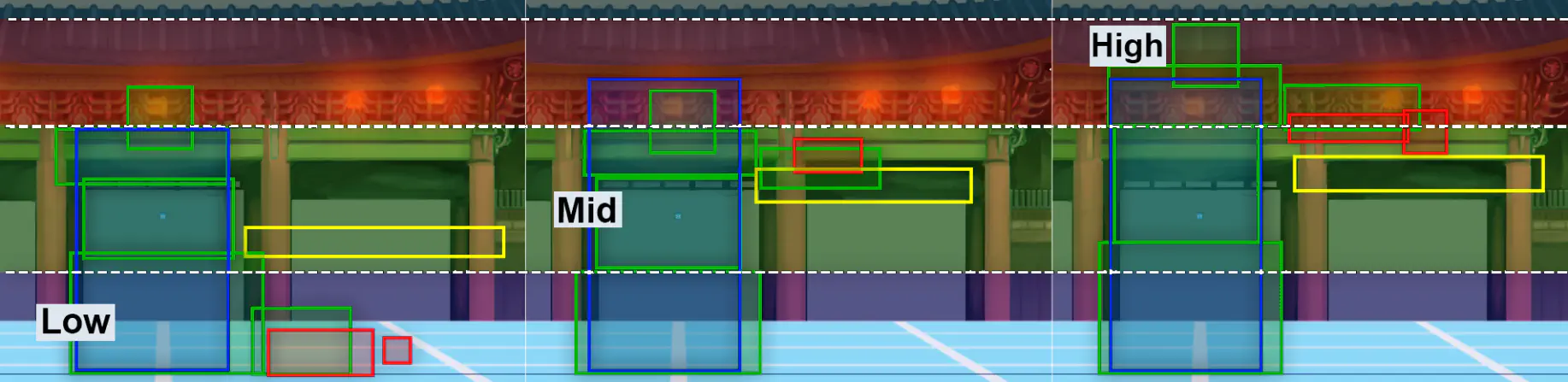

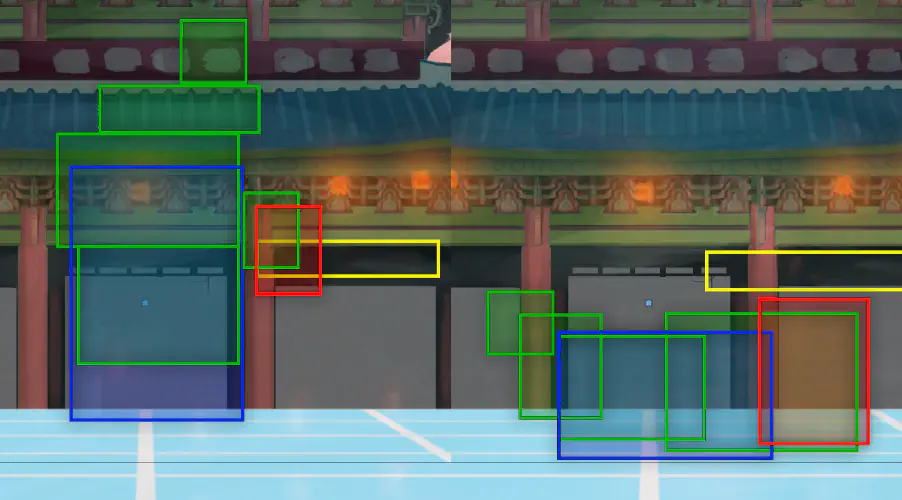

Lanes

So far we have been talking about hit and hurtboxes as if they are one dimentional, however in reality we are dealing with 2 dimentions (or even 3 if you are designing a full 3d fighting game). The way I deal with this by separating everything into several horizontal lanes:

Lanes don’t have concrete boundaries, however those categories are still useful when designing moves on a macro level. The main rule you need to consider is hitboxes from lane A can only reach hurtboxes from lane A.

There are several effects from lanes. Counter pokes and whiff punishes now require you to not only be able to reach the opponents preextended/extended hurtbox, but also your “reach” should be in the same lane.

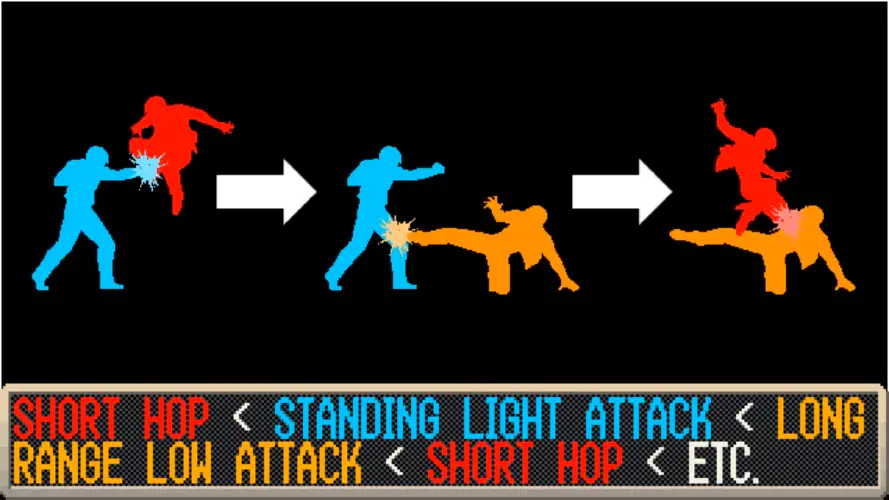

“Diagonal” Disjoint

Another effect to consider is disjointing a move in different lanes:

Frames are back to back. ‘Preextention’ hurtboxes are in the mid lane, while the hitboxes in the next frame are poking above to the high lane.

Anti airs are a perfect example of a disjointed lane attack2:

Hurtboxes are in the lower lanes, with hitboxes poking into the higher lanes.

Something that is less common in at least Street Fighter type games are diagonally disjoint moves that have the extended hurtbox in the upper layers and the hitbox in the lower layers. This is actually 1 one the reasons that make cr.mk such a key footsie move in those games - there are very few disjoint moves that could hit those moves from a different layer. This means that the only moves they can really interact with are only OTHER low moves.

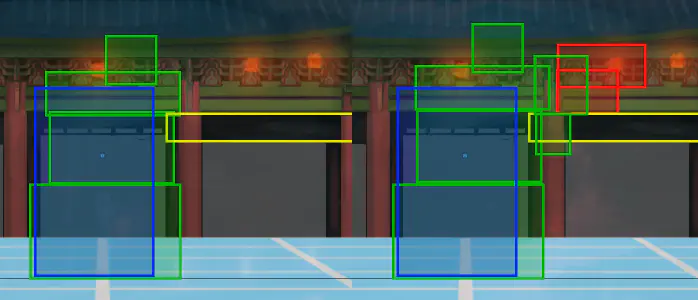

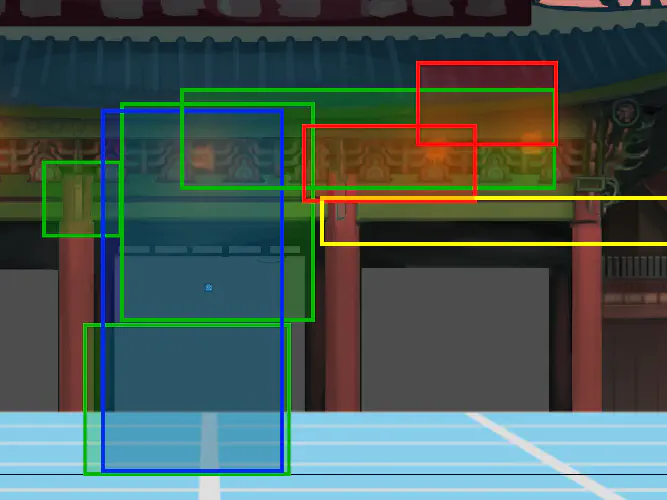

Low Profile and Low Crush

Left move: low crush - jumps over moves with hitboxses close to the ground. Right move: low profile - slides under mid and high lane hitboxes.

A low profile and low crush moves are a more extreme version of laning. In normal laning you would just have extention of the hurtbox in a specific lane, meaning moves that attack in that lane have easier reach, but attacks hitting in other lanes could still reach the main “idle” hurtbox. Low profile and high crush moves on the other hand remove parts of the “idle” hurtbox altogether making specific lanes attacks completely unable to “reach”.

A game that has this concept at its core is actually King of Fighters (image taken from the awesome guide3 to KOF by Dandy J):

Crouching low attacks low profile standing attacks. Short hops low crush low attacks. And standing attacks simply does not get affected by the low crush of short hops.

Use for variations

The main reason to use laning when designing hurtboxes and hitboxes is to add variety both to individual character’s moveset and interactions between characters. The “idle” hurtbox can also play a role in the nuances of lanes:

SF6 uses ‘flat’ laning in the idle hurtbox. SF3 uses more varied laning of the hurtboxes.

Simple ‘flat’ laning of the “idle” hurtbox is simpler and easier to manage, as you practically remove any nuance from laning and turn the interactions into a true 1d game. More layered laning would change up the interactions with moves. Moves hitting in the “middle” lane would require more reach than moves hitting the “top/bottom” lane. Crouching also has nuances, it extends the hurtbox of the “bottom” and “middle” lanes, but pulls back and down the head and “shoulder-line” hurtboxes, reducing and potentially killing the “top” lane attacks. This alone already gives you a “soft” rps between different types of attacks:

- standing high attacks have advantage over standing mid attacks

- standing mid attacks have advantage over crouching low attacks

- crouching low attacks have advantage over standing high attacks

Even more nuances appear when we consider the asymmetrical lanes that can be created from 2 characters of different heights and body builds.

While more lanes and nuances in them can increase the depth of a game, they also lead to more complexity. Because of that the game balance can be harder to manage and harder to control, which can lead to “emergent gameplay” (Check out Celia Wagar’s article) on emergent gameplay for a good read on the concept).

General Advice

This section covers different miscellaneous concepts regarding hurt/hit-boxes design. The subsections are not ordered, but all can be important.

Proximity guard

Proximity guard is a mechanic that prevents the opponent from walking away during the startup frames of the move, if the opponent is within a specific range (the proximity guard “hitbox”). The reason why you might want to use this is to buff poking attacks when dealing with whiff punishes. Depending on the whiff punisher’s movement speed they might be able to easily slip in and out baiting pokes with ease. So proximity guard gives you a tool to balance this. Proximity guard also helps with the spacing consistency of hitting whiff punishes, as if the whiff punishing player is already outside of the poking range - the proximity guard would keep them closer helping with the spacing margin.

The main way you balance with proximity guard is via the timing of appearance of the proximity guard’s “hitbox”. The sooner it appears the stronger the poke is against whiff punishes. The reach of the “hitbox” generally just needs to be as long as the actual hitbox of the move, and making it any longer would only help with the whiff punisher’s spacing margin.

Beware of making the proximity guard’s reach too long, as it would allow you to control the enemies movement potentially at full screen just by whiffing moves. This is viewed as janky, but it is an actual tech in Street Fighter 2, so you might actually consider emulating it, if you find the SF2 dynamic interesting to add in your game.

Relations with move properties

So far we have been only focused on the hitboxes and hurtboxes and we have been neglecting other move properties. In reality with the combination of both boxes and move properties we get the full nuance of gameplay and strategies you find in good fighting games.

Lets start with something simple - blockstun. Making a move unsafe on block is one of the easiest ways to add a drawback to a move. This is something you can use to balance for example invulnerable moves like DPs or supers that would win out against almost everything your opponent presses.

A more interesting example are counter pokes that are unsafe on block. Now you actually get range considerations as you want to hit in front of your opponent in order to clip their preextention frames, but you don’t want to get too close as you might get blocked and punished. You can use that to balance for example a counter poke move that very low whiff punish timing window, making it almost immune to general footsie gameplay, but giving it a weakness in the form of walk in and block. A variation on this concept are non-hitconfirmable cancelable moves. This gives the player a choice between safer lower damage keep out and risker higher damage keepout, letting them dynamically control the risk reward of the situation midmatch.

Another thing to consider is the reactivity for punishing a move that is unsafe on block. Keeping the hitfreeze of the move low and having the move have smaller amount of total frames would make punishing it on block harder. You can use that to balance out a move by giving it a niche of being able to overwhelm your opponent’s mental stack.

A different way you can balance out a very strong move in boxes attributes is via meter cost. This way the player pays the downside of the move upfront, and this can allow you to put in some absolutely broken (and fun) moves.

There are also some direct relations between the hitbox/hurtbox design of a move and its other properties:

- Longer active frames allows for more potential frame advantage on hit and block on meaty. If you don’t want this as part of a move, you can add variable frame advantage, so you get different amount frame advantage depending on the frame of the hit. This way you can counteract the meaty advantage, or make it EVEN stronger. For reference SF3:3S does this.

- Different properties on the extended hurtboxes. You might consider lowering the damage taken or increase the prorate when you are hit on an extneded hurtbox, and even removing some move properties. An example would be a dragon punch hitting a limb in 3rd strike: the dragon punch juggle property gets lost there and instead there is only hitstun, meanwhile the person who throw the dragon punch flies up into the air and gets punished as they land.

- Hitconfirmability - The longer the recovery, combined with a long hit stun the easier it is to hitconfirm a move.

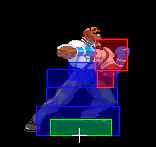

It is important to also consider the usage of the moves within the kit of the character as a whole. You don’t want to just have a bundle of random moves, but rather have a specific type of playstyle you are encouraging. An example from my game would be Biker’s st.hk:

It is absolutely brutal move in terms of reach in the top lane. It is really hard to whiff punish (no extended recovery) and even its preextention hurtbox is heavily disjointed with the total reach of the move. The catch with the move - would completely whiff on crouching characters unless Biker is very close (the lower hitbox has to clip the crouching head, which is pulled back). So the direct counter of this move are disjointed crouching moves that hit high, so all kinds of anti air moves work here. How does this tie to the Biker’s kit though? Biker is all about getting in close, and this moves would condition the opponent into crouching - this lets Biker directly walk in and start her pressure.

A last piece of advice I have is to create a jack of all trades/shoto character with middle of the road tools for everything. Even if you don’t want to have that kind of character it is useful for them to exist at least for testing. All moves exist and dynamics only exist in relation to other moves. So this character would act like a baseline for your balance of different kinds of tools.

Jumping attacks

I’m not going to cover the air game here as it is complex enough that it would require a whole article on its own. That being said the 2 things that make air game so complex are:

- variable movement speed: different types of jumps, drift (melty blood), air dashes lets you modify the movement speed of the move you are using dynamically. This completely changes how the reach of the move work, and you essentially have “infinite” amount of different moves you can create.

- because of the vertical movement, you can’t no longer reduce all boxes via lanes - now you are dealing with a true 2d game. This makes those moves incredibly complex.

Pressure?

How about covering pressure? The reality is pressure doesn’t really care a lot about boxes. Outside of low crush and low profile moves, the only other thing that matters is startup of the move. Pressure is played at close distances so most moves would reach, though for pressure at mid ranges reach can still play a role. However the main factor that control how pressure is played are the rest of the properties that moves have - damage, hit/block advantage, cancelablitiy, etc.

Relations with move animations

Most of the relations between the hit/hurt boxes and animations have to do with gamefeel rather than gameplay. The main exception is reactivity. This depends on the timing of keyframes that confirm or mask which move you are doing in order to change how many frames you have to react to the move. You can either put this frame right at the start of the move to make it easier to react to, or later on to make it harder. Another trick is to have 2 or more moves with the same startup frames and require different types of reactions, in order to hinder reactivity. Reactivity is downside you put or remove from moves in order to balance them, so use it with intention, rather than randomly put it on moves.

As for some general advice for gamefeel:

- Telegraph moves ending - this is important on longer moves, especially when you don’t have the budget for a lot of inbetween frames. You want to have a telegraph somewhere before or at 15f from the ending of the move to let players time an input right after the current move simply on reaction. Otherwise the move would feel stiff and locked down, because the player would not have a good feel of how long the move actually goes on for. Additional telegraphs are also useful from the 15f mark onwards to the end of the move. The telegraphs does NOT have to be a complete inbetween frame, they can be minor changes to the sprite, maybe movement in the hair or clothing, whatever is cheap to implement. They might even be a visual effect you can reuse for every character.

- Static Hurtboxes - sometimes an animation would have a lot of movement that you might not actually want to put in the hurtbox due to design reasons. An example for that can be taken from SF3’s ken’s cr.mk4:

The hurtbox keeps the old position, regardless that Ken has already dipped closer to the ground. And you can get away with holding this displaced hurtbox for quite a long time - 14 frames in the ken’s example. The only important thing is that you start from “accurate” hurtbox and end with an “accurate” hurtbox, but you can hold a static hurtbox to have leeway with your animations.

- Most important thing for making hit/hurtboxses feel right is to line up the extremes. You want to pay more attention to lining up the edges of the sprite and the boxes. In general you want to prefer to making the boxes reach a bit shorter than the sprites, rather than making them reach longer. If you make them overreach you would be hitting the air and it would look like you are hitting your opponent with telekinesis punches - this definitely looks like jank. On the other hand having the sprites touch slightly looks more acceptable. Another element you can play more freely is vertical positioning, you have a lot of leeway in nudging hurt and hitboxes up and down. This can help you a lot with getting the exact lanes you want for your design.

Conclusion

Ultimately the goal behind boxes design is to create the interactions that you want! You want to take 2 moves and have them work to suit your overall design, and then take this and extrapolate it for the whole network of moves you get. Even with all the information covered in this article it might be daunting to get started with this design. So a key advice I have is to go and analyse the boxes of your favourite fighting games. Look at how your favourite interactions work in those games, and use the concepts and attributes from this article to describe and understand how those moves are designed and function.

Thanks to Celia Wagar for improving the visual examples of the hurt/hit-boxses.